Plants are everywhere. They fill gardens, line streets, and sit on kitchen counters. But not all plants are built the same way.

Some have one seed leaf while others have two. This simple difference shapes how they grow, what their flowers look like, and even how their roots spread underground.

The distinction matters more than most people realize. It affects everything from the food on dinner plates to the grass underfoot.

Understanding this split helps explain why rice grows differently from beans, and why tulips look nothing like roses. The plant world follows patterns, and this is one of the biggest.

What are Monocots?

Monocots are flowering plants that start life with a single seed leaf, called a cotyledon. This group includes some of the most important crops and ornamental plants found around the world today.

Common Examples:

- Rice: A staple grain feeding billions of people across Asia and beyond.

- Wheat: The backbone of bread, pasta, and countless baked goods.

- Maize: Also known as corn, used for food, animal feed, and industrial products.

- Banana: A popular tropical fruit with soft, sweet flesh inside a protective peel.

- Lily: An ornamental flower known for its large, showy blooms and sweet fragrance.

Key Characteristics:

- One cotyledon: Seeds contain a single embryonic leaf that emerges first during germination.

- Parallel leaf venation: Veins run alongside each other from base to tip without branching networks.

- Fibrous root system: Thin, hair-like roots spread out rather than growing one deep taproot.

- Scattered vascular bundles: Internal transport tubes are arranged randomly throughout the stem, not in rings.

- Flower parts in multiples of three: Petals, sepals, and other flower structures appear in groups of three or six.

What are Dicots?

Dicots are flowering plants that begin with two seed leaves, or cotyledons. They make up the larger group of flowering plants and include many familiar vegetables, fruits, and decorative flowers.

Common Examples:

- Bean: A protein-rich legume that grows in pods and comes in countless varieties worldwide.

- Pea: Small, round green seeds eaten fresh or dried, often found in garden patches.

- Sunflower: Tall plants with large, bright yellow blooms that follow the sun’s path across the sky.

- Mango: A sweet, juicy tropical fruit with smooth flesh and a large central seed inside.

- Rose: An iconic flowering shrub cherished for its fragrant, layered petals in various colors.

Key Characteristics:

- Two cotyledons: Seeds contain two embryonic leaves that provide initial nutrition for the sprouting plant.

- Reticulate leaf venation: Veins form branching, net-like patterns that spread across the entire leaf surface.

- Taproot system: One main root grows deep into the soil with smaller roots branching off from it.

- Vascular bundles are arranged in a ring: Internal transport tubes form a circular pattern inside the stem.

- Flower parts in multiples of four or five: Petals and other flower structures typically appear in groups of four or five.

Structural Differences Between Monocots and Dicots

Monocots and dicots differ in four main areas: roots, stems, leaves, and flowers. Each structure reveals distinct patterns that separate these plant groups.

Roots

Monocot roots form fibrous networks that spread horizontally near the soil surface. Dicot roots develop a single thick taproot that penetrates deep underground.

This difference affects water absorption, anchorage, and how plants survive droughts or strong winds in varying conditions.

Stems

Monocot stems have vascular bundles scattered randomly throughout their structure, making them more flexible.

Dicot stems arrange these bundles in organized rings, allowing for secondary growth. This explains why dicots can develop thick, woody trunks while most monocots stay relatively thin and herbaceous.

Leaves

Monocot leaves show parallel veins running from base to tip without branching. Dicot leaves display net-like vein patterns that branch and interconnect across the surface.

Leaf shape, edge patterns, and overall structure also vary significantly between these two groups, affecting photosynthesis efficiency.

Flowers

Monocot flowers have parts arranged in threes or multiples of three, like six petals.

Dicot flowers typically feature parts in fours or fives. This mathematical pattern extends to sepals, stamens, and other reproductive structures, making flower identification relatively straightforward for botanists.

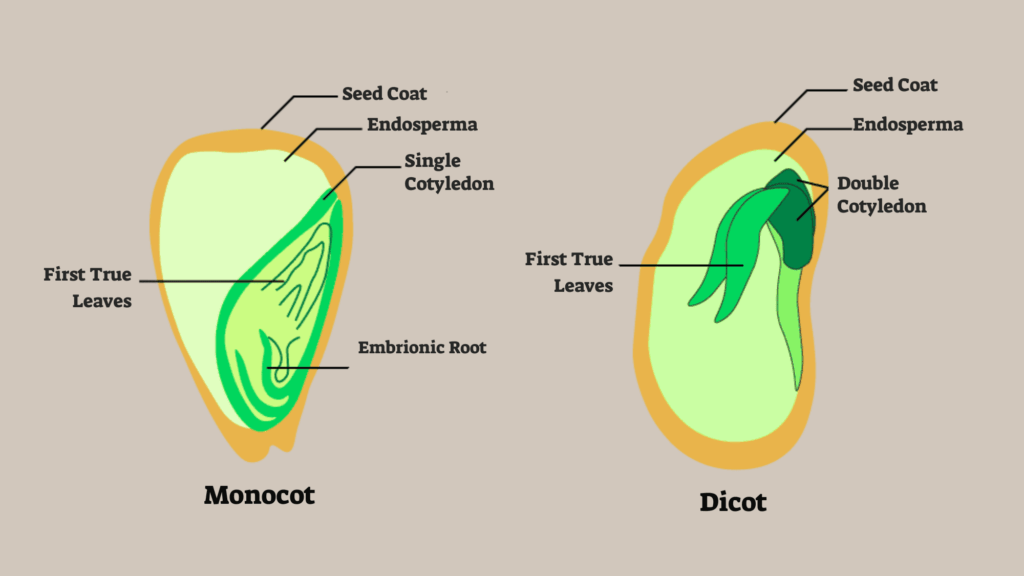

Embryo and Seed Structure in Monocot vs Dicot

The most basic difference between monocots and dicots starts inside the seed itself.

When a seed forms, it contains an embryo that will eventually grow into a new plant. This embryo includes cotyledons, which are the first leaves that emerge during germination.

Monocot seeds have just one cotyledon. This single seed leaf absorbs nutrients from the endosperm, a tissue that stores food for the developing plant.

The cotyledon stays underground in many monocots, transferring energy to the growing shoot.

Dicot seeds contain two cotyledons. These paired seed leaves often emerge above ground and may turn green, performing photosynthesis briefly before true leaves develop.

In some dicots, the cotyledons store nutrients directly rather than relying heavily on separate endosperm tissue. This structural difference influences how quickly seedlings establish themselves and begin independent growth.

Importance of Monocots and Dicots in Agriculture and Ecosystems

Both plant groups play critical roles in feeding the world and maintaining healthy ecosystems.

Monocots provide essential grains like rice, wheat, and corn that form the dietary foundation for billions of people. These crops supply carbohydrates, energy, and basic nutrition across continents.

Dicots contribute protein-rich legumes, fruits, vegetables, and oilseeds to human diets. Beans, tomatoes, potatoes, and soybeans offer vital nutrients and dietary diversity.

Beyond agriculture, both groups maintain ecological balance. They prevent soil erosion, cycle nutrients, produce oxygen, and provide habitats for countless organisms.

Grasslands dominated by monocots support grazing animals, while dicot forests create complex ecosystems. Together, they sustain life on Earth through food production and environmental stability.

Conclusion

Understanding the split between monocots and dicots opens up a new way to see the plant world. Their structural differences run deeper than appearances, affecting root systems, stem growth, and flower arrangements.

Next time someone bites into corn or picks a rose, they’re interacting with plants that evolved along separate paths millions of years ago.

These distinctions matter for farmers choosing crops, gardeners planning spaces, and scientists studying plant biology.

The natural world follows clear patterns, and recognizing them makes everyday surroundings more meaningful and connected.